When Historical Fiction Meets Political Turmoil… A Ladies’ Tearoom And The Road To Downing Street.

It has been a very strange experience these last few weeks, putting the final touches to a novel about women’s long, hard struggle to achieve the vote, while watching the political rollercoaster here in the UK – one that has led to a female Prime Minister, and Home Secretary, something almost unthinkable not so long ago.

It has been a very strange experience these last few weeks, putting the final touches to a novel about women’s long, hard struggle to achieve the vote, while watching the political rollercoaster here in the UK – one that has led to a female Prime Minister, and Home Secretary, something almost unthinkable not so long ago.

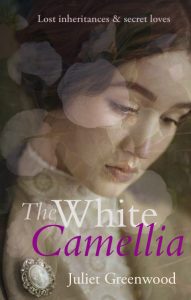

Much of my research for ‘The White Camellia’ (published by Honno Press this September) has been on the suffrage movement, the peaceful organisation that worked for decades before the violence of the suffragettes, not only to ensure both men and women had the vote, but also to give women a voice and a means of controlling their fate.

When the movement began, even the majority of men had no vote, and women had no legal existence of their own. They belonged to a father, then a husband, who ruled them, and spoke for them. The only career open to middle class women was that of a wife and mother.

When the movement began, even the majority of men had no vote, and women had no legal existence of their own. They belonged to a father, then a husband, who ruled them, and spoke for them. The only career open to middle class women was that of a wife and mother.

Many of the poorest, such as milliners, were so poorly paid they could not make ends meet however hard they worked, often dipping in and out of prostitution as a means to survive, or supplementing a husband’s income by low paid work on top of their heavy load of domestic chores. Women were also barred from education and the professions, being argued as too weak in the head to be able to cope with either. Nothing worse than a loud-mouthed woman who didn’t know her place.

It’s sometimes difficult to remember the rapid change that has taken place in women’s lives in – if you consider the history of humanity – a very short space of time. The Victorian era, and even 1909, when The White Camellia is set, can seem so long ago it bears little relationship with the present.

But I am the same age as the new British Prime Minister, Theresa May, and both my parents were born before 1928 – the year when all men and women over 21 finally achieved the vote. My parents married late, and were late having children, but that’s still a huge change, and writing the book has made me realise just how much their attitudes and expectations were shaped by their time.

It’s something I found I was able to draw on while writing the novel, along with the attitudes still prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s when I was growing up, and which had, in essence, not changed a great deal between the end of the Victorian era.

Women were still expected to marry and give up careers on marriage – and try and get a mortgage, or even a credit card, without a male signature, and you soon knew how far we had come. More than that, women were seen as frivolous, a joke, with nothing serious to say.

Mansplaining ruled, as did the Benny Hill version of womanhood: to be automatically chased around the desk when young, irrelevant when ‘old’ (i.e. 30). It was a time when it was as unthinkable as it had been in 1909 that women could regularly appear in public as respected scientists, journalists and academics, let alone taking the most powerful positions in government.

We might think we’ve left those bad old days behind, and that they don’t matter. But they do. Ask Cambridge professor, and brilliant communicator, Mary Beard, who is still insulted in the vilest terms for refusing to varnish her age (the same as Theresa May’s and mine) into an imitation of youth, and for speaking her mind. Still nothing worse (in some quarters) than a loud-mouthed woman who doesn’t know her place.

What these last weeks have also brought home to me is just how the way history is told shapes the way we see ourselves. When I started my research, I had only heard of the suffragettes. They were incredibly brave, and many died for their beliefs, but the suffrage movement fought for fifty or so years, and won many battles – including ensuring members of the UK parliament voted overwhelmingly for women to have the vote – and yet is scarcely heard of at all.

It was the failure of democracy when that vote was ignored (twice, in fact) that can be seen to lead to the frustration and increasing violence of the suffragettes – and they are not the first, or the last, to react in such a way.

Yet the overwhelming view of the fight for the vote remains the last few years of violence. The suffragists feared that such violence would simply reinforce the stereotype of the hysterical female, creating havoc and throwing herself under horses if she couldn’t get her own way, rather than rational, hard-headed civil disobedience and campaigning of the suffrage movement.

Many of the peaceful suffragists and campaigners also risked physical violence, and won the right to education, to legal protection and the ability to enter the professions, while still having no legal existence of their own, no right to vote, and being classed along with children and the insane.

I feel even more passionately than I did when I began writing ‘The White Camellia’ that it is vital for such women’s voices to be heard. Perhaps as (in the immortal words of MP Ken Clarke) one ‘bloody difficult woman’ takes over the post of PM, it is time, regardless of political allegiance, to reconsider the many bloody difficult women who fought, not only for women to have the vote, but for also for our voices to be taken seriously, as intelligent, cool-headed and deeply responsible human beings – and a force always to be reckoned with.

Certainly when I began writing ‘The White Camellia’ (only a couple of years ago!), I never imagined that by the time it was published there would be so many women in positions of power, and so visible in politics. The ladies of the White Camellia ladies’ tearooms, both the suffragists and the suffragettes, are definitely rattling their teacups – and watching closely.

—

The White Camellia

Honno Press – 15th September 2016

In 1909, the White Camellia ladies’ tearooms were one of the first places women could go alone without causing scandal, and where both the suffrage, and early suffragette, movements could grow.

Bea has lost everything after her father’s bankruptcy. The family has to leave Tressillion in Cornwall, to live in London, and everyone expects Bea to rescue her mother and sister by marrying her wealthy cousin. A chance visit to the White Camellia opens new worlds to her, as she finds herself drawn into the suffrage campaign. But can she follow her heart without betraying her family?

Sybil, who has made her fortune in America, buys the Tressillion estate and is determined to reopen the goldmine that killed Bea’s father and brother. Why does she hate Bea’s family? Who is the man watching her? The secrets of Tressillion will eventually force Bea and Sybil together. Both threatened by a terrible danger, will they be enemies or allies?

—

Juliet Greenwood is the author of two previous novels for Honno Press, both of which reached #4 and #5 in the UK Amazon Kindle store. ‘Eden’s Garden’ was a finalist for ‘The People’s Book Prize’ and ‘We That are Left’, ‘We That are Left’ was chosen by the ‘Country Wives’ website as one of their top ten ‘riveting reads’ of 2014 , was one of the top ten reads of the year for the ‘Word by Word’ blog, and was a Netmums top summer read for 2014.

Juliet has always had a passion for history, and in particular for the experiences of women, which are often overlooked or forgotten. She lives in a traditional cottage in Snowdonia, and loves gardening and walking.

Buy The White Camellia HERE: UK US

‘We That Are Left’, Honno Press, 2014

‘Eden’s Garden’, Honno Press, 2012

The Suffrage Ladies’ Tearoom Blog: https://suffrageladiestearoom.com/

Find out more about Juliet:

Website: http://www.julietgreenwood.co.uk/

Blog: http://julietgreenwoodauthor.wordpress.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/juliet.greenwood

Twitter: https://twitter.com/julietgreenwood

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/julietgreenwood/

Category: On Writing

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post