The government warned federal judges in 2016 that their attempts to create a catch-and-release policy for illegal immigrant families would lead to children being “abducted” by migrants hoping to pose as families to take advantage.

The court brushed aside those worries and imposed catch-and-release anyway.

Two years later, children are indeed being kidnapped or borrowed by illegal immigrants trying to pose as families, according to Homeland Security numbers, which show the U.S. is on pace for more than 400 such attempts this year. That would be a staggering 900 percent increase over 2017’s total.

“The eye-popping increase in fraud and abuse shows that these smugglers know it’s easier to get released into America if they are part of a family and if they bring unaccompanied alien children,” said Katie Waldman, a Homeland Security spokeswoman. “These loopholes make a mockery of our nation’s laws, and Congress must act to close these legal loopholes and secure our borders.”

Abductions are one of the more startling aspects of the surge in border crossings, which is testing the Trump administration just as a surge tested President Obama in 2014.

While the previous administration struggled to settle on a policy, President Trump and his team have shown little hesitation in pushing for strict enforcement, announcing a zero-tolerance approach that includes prosecuting adults who attempt to jump the border without going through an official border crossing.

The administration says it’s the best way to encourage people not to make the dangerous journey north — particularly if they were going to bring children.

Most of those cases are indeed legitimate families, and the parents may end up facing criminal charges, leading to separation, under the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy.

But in a growing number of cases, illegal immigrants who aren’t even related to the children are showing up and fraudulently claiming to be families.

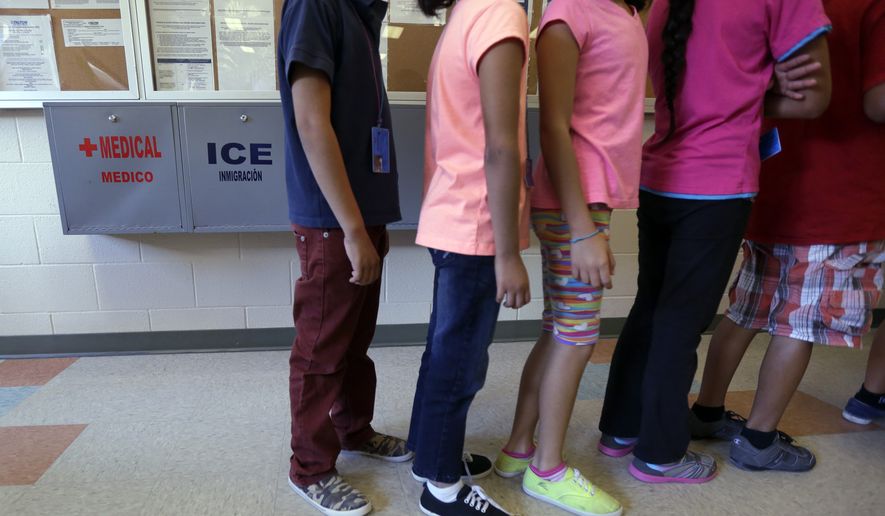

Homeland Security recorded 191 cases of children having to be separated because of fraudulent family claims during the first five months of fiscal year 2018. That already eclipses the 46 cases reported for all of 2017.

The practice seems particularly popular among Hondurans, based on a sampling of cases that The Washington Times has learned of in recent months. Honduran men on multiple occasions have attempted to cross into Texas with unrelated children in tow — and with bogus birth certificates claiming to show parentage.

While some of the cases involve abductions, other cases involve children whose parents knowingly lend them to friends looking to pose as a family.

Homeland Security is tight-lipped about individual cases but has publicly acknowledged the problem.

“We’ve had many cases where children have been trafficked by people who weren’t their parents,” Thomas D. Homan, the acting chief at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, told Congress on Tuesday.

Attempts to smuggle children are by no means new, but there does seem to be a shift.

Cases reviewed by The Times from earlier this decade usually involved a U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident smuggling for pay or as a favor to a particular child or family.

In one case that came before U.S. District Judge Andrew S. Hanen, the judge who is hearing Texas’ challenge to the Obama-era DACA program, a woman was convicted in 2013 of trying to smuggle an unrelated 10-year-old girl from El Salvador into the U.S. using one of her own daughters’ birth certificates. The 10-year-old girl’s mother, an illegal immigrant living in Virginia, paid $6,000 for the attempt.

In the latest rash of cases, however, it is illegal immigrants who are doing the smuggling and using the children for their own benefit, hoping to appear more sympathetic to American law enforcement to try to earn easier treatment.

Border Patrol agents are also seeing instances of parents with multiple children splitting up to enter the U.S., said Brandon Judd, president of the National Border Patrol Council.

He said the parents know that if they came as a couple along with their children, one parent might be separated, leaving just the other parent with the children. But if they cross individually, each with a child, agents won’t separate the child from someone who appears to be a single parent.

Authorities attribute the surge to an overall increase in attempts to jump the border and to a series of court rulings at the end of the Obama administration that created the family catch-and-release policy.

In those rulings, U.S. District Judge Dolly M. Gee decided that a Clinton-era court agreement known as the Flores Settlement, which previously applied only to unaccompanied alien children, should also apply to juveniles who arrive at the border with their parents.

She ruled that the children should generally be released from Homeland Security custody within 20 days. But she also ruled that the children are best-served when they are placed with their parents, so it made sense for the entire family to be released from custody.

The Obama Justice Department warned the courts that created a perverse incentive for people to bring children on the dangerous journey — and in some cases to kidnap children to pose as families.

“When people now know that when I come as a family unit, I won’t be apprehended and detained — we now have people being abducted so that they can be deemed as family units, so that they can avoid detention,” Leon Fresco, deputy assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s office of immigration litigation, told the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at the time.

Judge Gee’s office declined to comment Tuesday on the surge in kidnappings other than “to advise you to read the Flores settlement agreement.”

But Peter Schey, the lawyer who won the case before Judge Gee, said kidnappings aren’t as much of a problem as the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance prosecution policy.

“The number of children separated from their parents by human smugglers is a tiny fraction of the number of children being forcibly separated from their parents by the Trump administration,” Mr. Schey told The Times.

When families are caught under the new policy, he said, agents will isolate and interrogate the children, looking for evidence to use against their parents in court.

The parents often end up serving brief jail time, but the children by then have by then been shipped into the foster care system, leaving the parents with “no idea how to track down their children who DHS yanked from the parents’ custody.”

“The policy is irrational and inhumane,” Mr. Schey said.

Democrats on Capitol Hill also questioned how Homeland Security was deciding which family claims were deemed fraudulent.

Rep. Nanette Diaz Barragan, a California Democrat who as a lawyer handled some asylum cases, said some people who show up on the border are fleeing horrific circumstances back home.

“It is hard for some of these families, when they’re fleeing violence and they’re leaving their country. They’re not exactly saying, ‘Oh, let me get the documents to prove this is my child,’” she said Tuesday at a House Homeland Security Committee hearing.

“I’ll tell you right now if I had to go find something to prove my relationship with my child it would probably take me a little bit,” she said.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.